🎮 The Business Game Walkthrough: Level 1 – The VAT Dilemma

Welcome to Level 1 of the Business Game, where we dissect how Value Added Tax (VAT) impacts a company and its owner. We’ll be focusing on a fictional manufacturer,

Dryden, which produces high-staff input goods with minimal materials and sells directly to consumers. This structure makes Dryden highly sensitive to VAT changes.

The Core Problem: Price Sensitivity

The price of Dryden’s dehumidifier is typically set at £500 + VAT.

- A current UK VAT rate of 20% makes the consumer price £600 (or often £599.99).

- A lower VAT rate of 10% would make the price £550.

- A higher VAT rate of 25% would make the price £625.

Consumers are sensitive to these price changes; as prices go higher, they are less willing and less able to buy, instead finding alternatives, delaying purchases, or making do without. This inverse relationship is known as price elasticity. Our model uses a high price sensitivity: for every 5% increase in VAT, there is roughly a 10% decline in total sales. This is based on the suggestion that price elasticity for UK electronic goods is between -1.5x and -2x.

Scenario 1: Starting Point – VAT at 20%

To begin, we set the starting conditions:

VAT at 20%, Corporation Tax at 25%, and Income Tax at 0%. The goal for the business owner is to reach a personal wealth of £250k by Year 5 with an annual dividend of £100k needed each year.

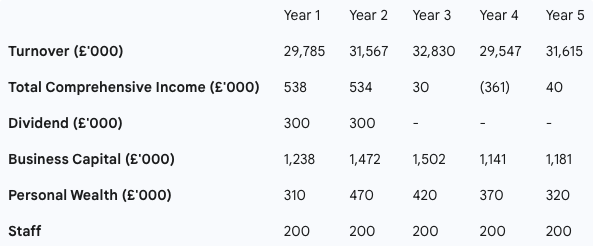

Outcome 1A: Taking High Dividends (£300k in Years 1 & 2)

Result: The business does well initially but struggles in Years 3-5, with Year 4 resulting in a loss. The business owner reaches their £250k wealth goal. However, this success is an illusion. With a £4.5 million loan to refinance, the stagnant Business Capital (£1.181m vs. initial £1m) means the company cannot upgrade its machinery or pay back the debt, facing eventual insolvency. The owner needs to hold back dividends and grow the company’s capital base.

Outcome 1B: Prudent Management (Reducing Staff/Dividends)

Result: By holding back dividends and reducing staff from 200 to 190 in anticipation of slowing sales, the Business Capital grows sustainably to £2.456 million. The business remains profitable, even in the weaker Year 4. The drawback is that the business owner does not meet his personal wealth commitments within the 5-year period.

Scenario 2: The Brutal Hike – VAT at 25%

What happens if the government increases VAT to the maximum game level of 25%?

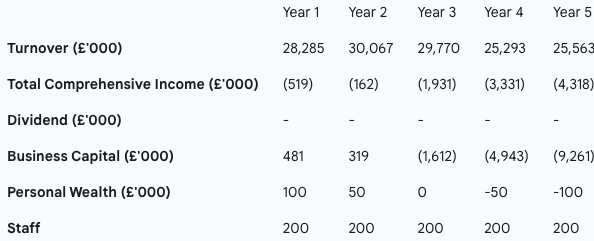

Outcome 2A: The Terminal Outcome (No Dividends, Full Staff)

Result: The business is brutalized. Sales decline due to the high 25% VAT being passed to consumers. The company goes bust in Year 3 as capital runs out, even without the owner taking a dividend.

Outcome 2B: The Survival Grind (Reducing Staff/Taking Dividends)

The business owner is forced to retrench, drastically cutting staff to survive, whilst also taking a minimal dividend to prevent running out of personal savings.

Result: The company just about stays afloat, but Business Capital is depleted to £262k. Staff numbers are cut by 40% (from 200 to 120), meaning the remaining staff are overworked. The business is running on a wire and the owner should look to sell before all capital is gone.

Scenario 3: The Growth Engine – Reducing VAT to 15%

What if the government lowers VAT to 15%? A 15% VAT rate means Dryden either makes an extra 5% on goods or sells 10% more units (in the model).

Outcome 3A: Sustainable Growth (Fixed Staff, Fixed Dividend)

Result: This is a healthy business. The owner comfortably reaches the personal wealth goal of £250k. Crucially, the Business Capital grows massively to over £10 million, allowing the company to fully pay down its £4.5 million bank loan.

Outcome 3B: Accelerated Growth (Increased Staff and Dividends)

The healthy capital base allows the business to hire more staff (5-15 new staff each year) and pay a larger dividend in Year 5.

Result: The business owner is highly satisfied and the staff grows by 27.5% (from 200 to 255), helping to meet increased orders and facilitate new product research.

Final Question: Is this just a trade-off with the Government?

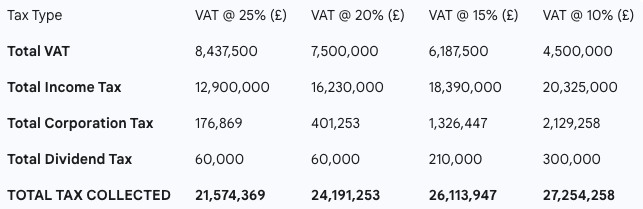

The final question is whether a healthier business just means a poorer government. The model suggests that the lower VAT rates actually lead to better overall tax collection.

The drop in VAT revenue is more than compensated by a massive rise in Income Tax (from higher employment) and Corporation Tax (from higher profits).

Conclusion:

- The 25% VAT rate collects the most VAT but the least total tax.

- The 10% VAT rate, compared to the current 20% rate, leads to a higher overall tax collection.

- This happens because a high tax burden prevents businesses from growing, hiring people, or generating profit and dividends. When a business is profitable and growing, tax is collected through other, more sustainable methods like Income Tax due to a larger workforce.

This simulation suggests that for products with high price sensitivity, governments make a mistake by averaging the impact across the economy and fail to account for how a high VAT rate can stifle job growth and overall profitability, reducing the total tax take.